In traditional religious teachings, sin is often portrayed as an inherent flaw within human nature or a taint upon the physical world, the body, and matter itself. But in Gnostic texts, this view is redefined: sin is not something “out there” or intrinsic to human existence. Instead, Jesus tells his followers, “There is no sin. It is you who makes sin exist when you act according to the habits of your corrupted nature. This is where sin lies.” Sin, in this view, is a creation of our own perceptions and choices rather than an unavoidable mark of our humanity.

The Gnostic perspective challenges us to look at our own role in the creation of sin. Historically, this idea of projecting sin onto others has fueled persecution, judgment, and even violence. From the burning of “heretics” to mass executions of those deemed “evil,” many have justified harmful actions as a way to “purify” or “protect” society from perceived corruption. By projecting sin outward, we create a false separation between the “pure” and the “impure.” This mentality, the Gnostics suggest, leads to suffering and perpetuates the cycles of conflict and alienation that plague humanity. “You see the splinter in your brother’s eye but do not see the beam in your own,” as Jesus teaches, reminding us to look within before casting judgment on others.

In the Gospel of Mary Magdalene, Jesus offers a radical perspective on sin, not as an external force but as an internal creation: “Do not add more laws to those given in the Torah, lest you become bound by them.” This highlights the need for liberation from dogmatic thinking, which only deepens attachment to a rigid, fear-based approach to life. Sin, as described in these teachings, is a deviation from our alignment with the divine essence within us, a concept also echoed in Paul’s letter to Titus: “To the pure, all things are pure; but to those who are corrupted and do not believe, nothing is pure.”

This Gnostic understanding resonates with the original Greek word for sin, “hamartia,” which means “to miss the mark.” Sin, then, is about losing our orientation toward our divine nature. When our senses, intelligence, and emotions become misaligned, we interpret the world through a distorted lens, mistaking our subjective perceptions for reality itself. Meister Eckhart, a mystic whose teachings align closely with Gnostic thought, emphasized that true understanding requires the surrender of these distortions: “If you do nothing, truly nothing, God cannot help but come into you.” This idea suggests that by emptying ourselves of judgments, opinions, and preconceived ideas, we create the space necessary for divine presence to enter.

The Gnostic approach to sin also challenges us to recognize that “matter is not evil; it is the corruption of thought that creates evil.” The physical world, body, and matter are not inherently sinful; they are neutral. It is our misuse, misunderstanding, or misguided desires that can lead to suffering. Sin, then, is not something outside of us but rather a disorientation within us that comes from seeing ourselves and the world through a limited perspective.

This leads to what Gnostic teachings call “corrupted nature”—not as a condemnation of our being but as a description of how our biases and assumptions create a “second nature” that clouds our true essence. We begin to see our projections as truth, mistaking them for absolute reality. Søren Kierkegaard, the existential philosopher, echoed this insight, warning against “making the relative absolute and the absolute relative.” This misinterpretation lies at the heart of human suffering, as we become trapped by our limited perceptions and misguided identifications.

Paul’s writings in Romans offer a similar insight, advocating for liberation from external laws that bind us to fear and judgment: “But now we are delivered from the law, for we became dead to that which bound us.” The Gospel of Mary expands on this, encouraging believers not to add new laws or impose rigid rules upon themselves, for laws should not be barriers to spiritual freedom. In Hebrew, the word “saved” means “to breathe freely,” highlighting the liberation that comes when we transcend the ego and rigid attachments to doctrine.

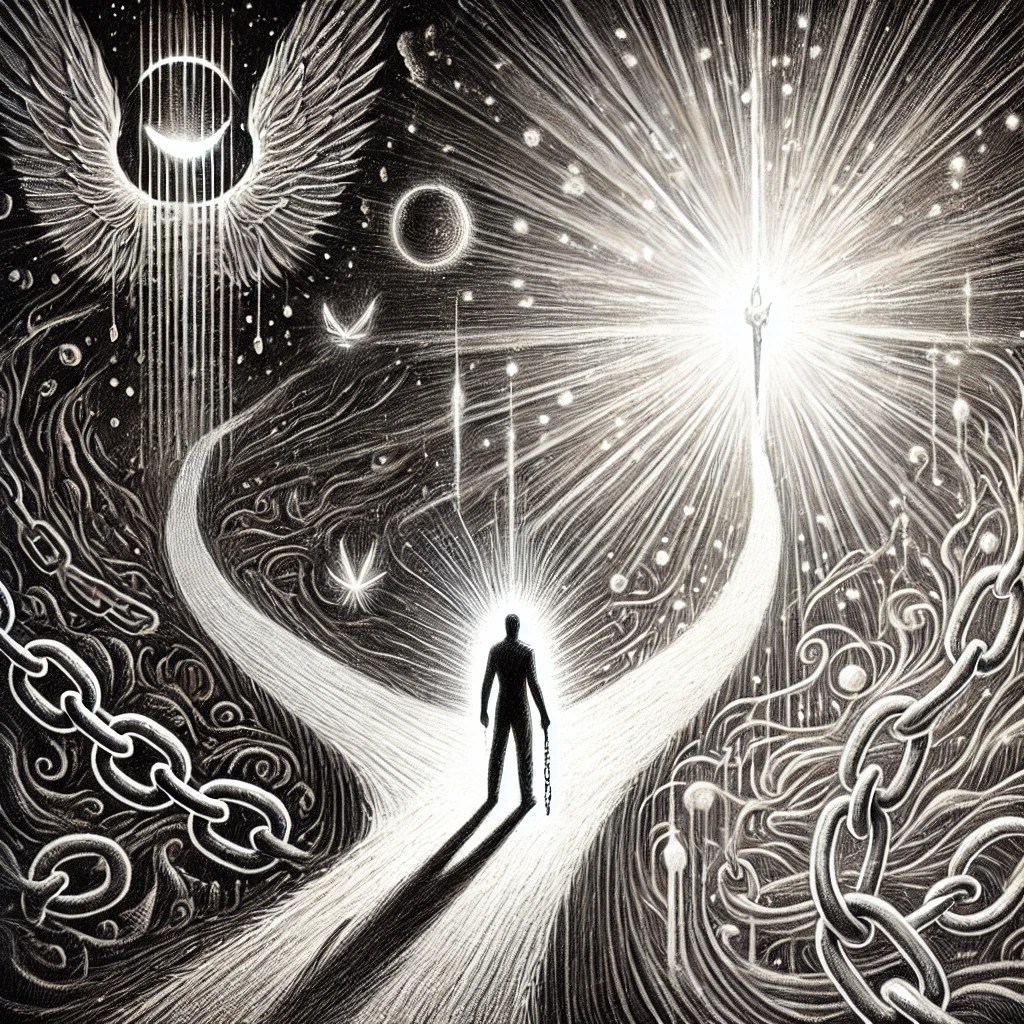

The ultimate teaching of Gnosticism here is that sin is an illusion born of misalignment. The only way to overcome it is to recognize and dissolve the false identities we cling to. The Gospel of Thomas captures this beautifully: “The Kingdom is inside of you, and it is outside of you. When you know yourselves, then you will be known, and you will understand that you are children of the living Father. But if you do not know yourselves, then you live in poverty, and you are the poverty.” This passage invites us to look within, to uncover our true selves rather than clinging to distorted images shaped by society and ego.

As we begin to take responsibility for our perceptions, we find that sin loses its power over us. Instead of seeing it as a mark upon our being, we understand it as a condition created by our own choices, thoughts, and attitudes. We realize that “all is pure to those who are pure.” This state of purity arises when we empty ourselves of inherited beliefs and learned behaviors, allowing us to reconnect with our divine source.

Only by letting go of these attachments can we return to our true state of wonder and openness, experiencing life not as objects bound by time but as dynamic expressions of the infinite. As Eckhart says, “If you leave, God can enter.” This is the invitation of Gnosticism: to leave behind the illusion of a fixed self, to break free from judgment, and to embrace the unbounded freedom of our true, divine nature. In this state, we no longer mistake fleeting perceptions for ultimate reality, but instead, we see ourselves as we truly are—expressions of divine light and being, forever one with the source.